In the past two decades, as new lanes and paths have sprouted throughout the five boroughs, bicycling in New York City–once considered a fringe activity–is now a mainstream transportation option. And now the city has the numbers to prove it. According to a new report by the New York City Department of Transportation, Cycling in the City, the number of daily bike trips throughout the city grew 320 percent between 1990 and 2014.

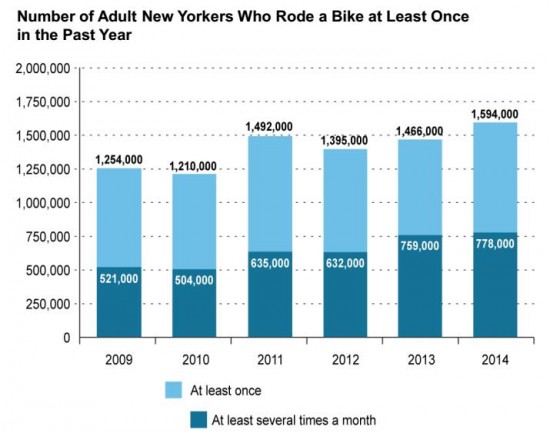

It’s not just daily cycling that’s growing: between 2009 and 2014, the number of New Yorkers who bike at least once a year rose by more than 340,000, and the number of those who bike at least a few times a month grew 49 percent. This indicates that the appeal of biking is even reaching those less experienced with cycling–outpacing the DOT’s ongoing investment in the city’s bike network.

Despite this growth, DOT shouldn’t take a victory lap just yet. While the expansion of the city’s bicycle network in the last few years is a welcome change, the department has watered down (or totally neglected) comprehensive bike lane treatments–shown to make street safer for all users–in some of its proposed street redesigns:

- Riverside Drive, a major bike route, ranks in the top third of Manhattan streets with the most collisions, yet a proposal to calm traffic and add pedestrian space between 116th and 135th Streets was delayed and then watered down after facing opposition from Manhattan Community Board 9. Bike lanes were altogether missing from the proposal.

- Farther north in Inwood, DOT recently re-striped only the northbound bike lane on Seaman Avenue, replacing the southbound bike lane with sharrows. The agency cited the street’s narrow width as the reason for the new design, yet managed to preserve two lanes for parked cars.

- Meanwhile in Brooklyn, instead of a coherent network of bike lanes, DOT proposed three different designs for bike lanes along Brooklyn and Kingston Avenues for three different community boards. And last year, a proposal for Fourth Avenue–one of the borough’s most deadly roads–didn’t include any bike lanes at all.

Despite this seeming indifference, DOT is fully capable of implementing high-quality bike infrastructure. Protected bike lanes along some of Manhattan’s major avenues and Queens Boulevard–formerly known as the “Boulevard of Death”–have changed how New Yorkers choose to move around the city by making it safer to bike and walk. There’s even a short raised bike lane along 7th Avenue in Times Square–similar to bike infrastructure seen in Copenhagen–which has eased biking through the congested corridor.

DOT’s commitment to install a record 17.8 miles worth of protected bike lanes in 2016 is a step in the right direction. But without a stronger alignment between the department’s stated goals and tangible results, it’s hard to envision the continued growth of biking in the coming years.

[…] Will Today’s Bike Network Development Enable Cycling in NYC to Keep Growing? (MTR) […]

Every politician who resists better bike lanes should be required to take their age 12-18 children, nieces, nephews, or grandchildren on the ride down 7th Avenue through Times Square, as shown in the video linked above.

only 50 miles of useful protected bike lanes ( PBL ) exist today. PBLs in NYC cost a paltry $500k per mile. a little more than 10% of CBD roadaay traffic are cyclists with less than 2% of roadway allocation.

spend $25 million to build 50 miles of PBL annually for next decade. results will be:

1) less congestion ( bikes take less space than cars )

2) better safety ( cars kill )

3) increased mobility ( cycling is more convient than driving for the 58% of NYC trips that are less than 3 miles )

[…] population. Without adequate investment and improvements to the city’s transit or safe streets network, however, it remains unclear whether such growth can be […]

[…] at least once in the past year. A comprehensive network of separated bike infrastructure would surely encourage more people to bike, yes, but it would also better protect those New Yorkers already riding the […]