Language is a powerful tool, and the specific expressions we choose can convey ideas with broad implications. But in the struggle over word choice, our discussions tend to narrow into a frame of reference which can instill bias.

Our conversations on transportation are no exception. For example, the practice of using the word “accident” to describe a traffic crash has recently earned its fair share of criticism, but it’s not the only problematic word we have in our day-to day transportation lexicon.

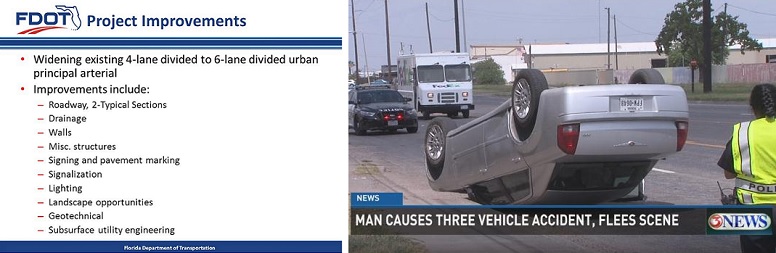

Much of our transportation language developed during the rapid shift to automobiles, so we sometimes contort our speech to favor drivers over everyone else. Look at any government document describing a proposed highway project, and you’ll see descriptions riddled with generic, positive sounding words like ‘improvement,’ ‘enhancement,’ or ‘upgrade.’ These words aren’t inherently problematic, but their proponents (perhaps unwittingly) abuse their rosy connotation to imply that a project is universally beneficial, regardless of its objectives.

This is a problem. Many transportation “improvements” benefit only drivers, which means they likely have some drawbacks for pedestrians, bicyclists and transit users. We should remind ourselves to ask, “improvements for whom?” and must demand greater specificity when describing the projects that impact our streets. After all, who wants to stand in the way of an “improvement”? If you don’t believe me, just try talking to an engineer.

Our transportation language does more than just obscure issues; it also affects how we view the people using our streets. The slogan “War on Cars” is a popular refrain repeated by those concerned about a perceived loss of deference towards people who drive. However, this reactionary phrase fails to address why so many people are dying on our streets.

Can using different words help us reimagine our streets? A group of advocates in Seattle thinks so. Instead of otherizing individuals by the mode they happen to choose, the group puts people first. Nobody is referred to as drivers, cyclists, or pedestrians; they’re people driving, people biking, or people walking. The renewed emphasis on the humanity of all road users has done wonders to improve the conversation on street safety in Seattle. Could a similar argument reframe the debate here in the New York region as well?

For advocates of safer streets and transportation choice, pro-car language bias can prove difficult to work around — even in the only U.S. city where a majority of households are car-free. History tells us, however, that language is infinitely flexible and by pushing to change the language around transportation, advocates can move the debate away from tired tropes and toward a discussion about promoting safety and choice.