At the tail end of New York City’s hottest summer on record, the federal Environmental Protection Agency delayed a decision on proposed stricter national standards for ozone that was expected at the end of August. There has been plenty of political heat over the proposed standard, which has the potential to put much of New York State in “non-attainment” (failing EPA standards), forcing agencies to find new ways to clean the air.

What Non-Attainment Means for Transportation

States must improve air quality in non-attainment regions by developing plans to tackle major pollution sources, including transportation. Being in non-attainment is hardly a transformative event. For example, all of New Jersey and Connecticut is in non-attainment for ozone, but that has not stopped huge road projects like the NJ Turnpike widening or Q Bridge expansion from moving forward.

But it can have significant effects. The NY State Department of Environmental Conservation’s “state implementation plan” caps parking in Manhattan’s central business district and was cited in a recent lawsuit which reduced parking in NYC’s planned Hudson Yards district. Regions in non-attainment also get funds from the federal Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality program (CMAQ), a large program typically used for transit, bike and pedestrian, and demand management projects. In our region, CMAQ funds have been used for projects as diverse as freight rail improvements in NJ, the purchase of shuttle buses in Norwalk, CT; and parts of the Harlem River Esplanade (park and bike/pedestrian path) in New York City.

A New Standard

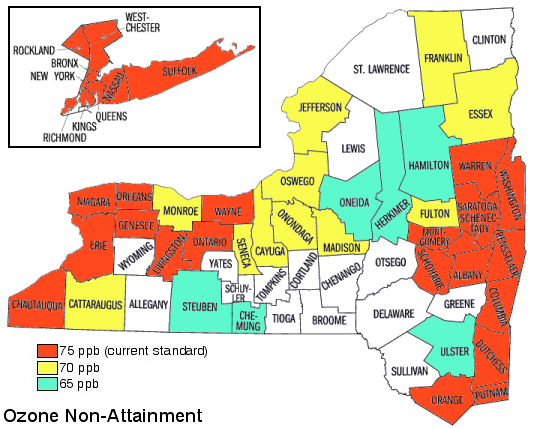

The current standard for ozone levels is 75 parts per billion (ppb) measured in an 8-hour period. In January, the EPA proposed a stronger standard, between 60 to 70 ppb. If adopted, this standard would be gradually phased in through 2030.

As the map at right shows, a stronger standard would mean a new state of affairs for less populated counties that have never been in non-attainment before. “Any new projects that add [road] capacity… will require some kind of offset or mitigation project to minimize or reduce vehicle emissions,” said Bill Tobin, principal transportation planner for the Ulster County Transportation Council, the municipal planning organization.

UCTC would have to produce different travel demand modeling and would need to better coordinate with planning organizations in surrounding counties, whose activities impact Ulster County’s air, Tobin said. He worried that “it will be burdensome to meet these requirements and continue performing our other daily responsibilities,” given staffing levels at the agency. On the positive side, qualifying for CMAQ funds will help the County move forward on much-needed transit, park and ride, and trail projects.

New standards would mean that New York would have to do more to reduce transportation emissions. To date, regulations like vapor capture nozzles on gas pumps and clean diesel requirements have helped, but “you can only revisit gas cans so many times,” says Mike Sheehan, who works on transportation issues in the NY State Department of Environmental Conservation. This year, New York joined other Mid-Atlantic and New England states in signing the Transportation and Climate Initiative, an agreement to “work collaboratively” in reducing transportation emissions. However, driving these efforts forward with effective implementation will depend on leadership from the next Governor.

Clean Air vs. Politics

The Clean Air Act directs the EPA to review the “national ambient air quality standard” for pollutant levels every 5 years. In 2008, the Bush Administration set the level at 75 ppb, ignoring the EPA’s own scientists, who had recommended a level between 60 and 70 ppb. Under the Obama administration, the EPA has re-examined the science behind the numbers.

But stronger, science-based ozone standards aren’t a done deal, and face pressure from industry and many politicians. Opponents have argued that stricter standards will incur higher compliance costs and negatively impact the economy. Two Democrats and all of the Republicans on the House Appropriations subcommittee even tried, unsuccessfully, to cut off federal funds that enable the EPA to reconsider the rule.

However, the abysmal air quality this summer in New York City has spurred many supporters to speak out, including the New York Times editorial board. As Tri-State board chair Rich Kassel recently pointed out in the Gotham Gazette, this summer NYC residents slogged through 27 air quality alert days when ozone levels put human health at risk; during an average summer the city sees fewer than 5 alert days. “It will be critical for Washington to take positive action on these necessary policy steps, and for New York to adopt a plan to finally meet EPA’s health standards for ozone, once and for all,” he wrote. The EPA is now expected to make a decision on the new standard by the end of October.

Image: TSTC using data from the NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation.

[…] people so we release less Co2 that pollutes our air. This can only be done by the effort of people. https://blog.tstc.org/2010/09/21/new-ozone-standards-could-mean-change-for-upstate-new-york/ Categories: Uncategorized Leave a […]