With two derailments at Penn Station in under two weeks, people are asking lots of questions: How did this happen? What could we have done differently? Do you really think we can handle all of these people on an already overcrowded PATH train?

Another question to ask might be, could we have avoided this if our spending priorities were properly aligned with national and local needs?

At the national level, it’s very clear that Republicans consider transit to be a local issue. Their platform includes the following language:

“One fifth of [the Highway Trust Fund’s] funds are spent on mass transit, an inherently local affair that serves only a small portion of the population, concentrated in six big cities.”

In the same spirit, the Trump administration’s budget blueprint proposes eliminating the New Starts program, which provides transit capital grants, stating “Future investments in new transit projects would be funded by the localities that use and benefit from these localized projects.”

This line of thinking displays a patent misunderstanding of the realities of our national economy and also belies good government calls for efficiency. Large U.S. cities (those with populations of 150,000 or more) generate about 85 percent of the country’s GDP. As we explained in 2014:

The ten largest metropolitan areas, which account for a quarter of the nation’s total population, produce more than a third of the national GDP. Taking a more visual approach, it is easy to see how vital metropolitan regions are to the economic vitality of the country:

This trend is only going to get stronger with a continued population and employment shift toward metropolitan areas. Study after study has shown that millennials want to move to cities where there are multiple transportation options available. At the same time research suggests that an increasing share of employment is shifting to city centers.

And with respect to the NYC metropolitan region, TSTC explained:

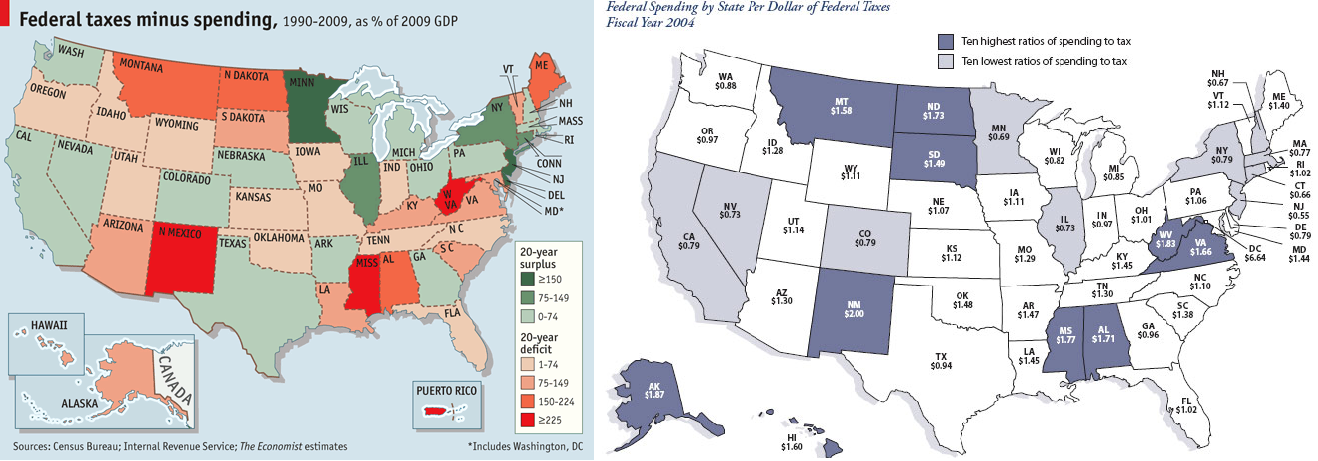

If the country were to be run like a business, the New York City metro area — the most productive “department” — would indeed be getting lots more funding. Yet for some reason, the opposite is true. In fact, states in the region receive the lowest return on federal taxes paid in the nation, measured as a percentage of state GDP, as well as tax dollars paid versus dollars received:

To remain as productive, more money is required to keep workers moving – you can’t go to work if you can’t get to work. Ridership numbers for the New York City metropolitan area’s transit systems are high, carrying more people than the nation’s busiest roadways. In fact, the combined ridership is over 4 billion trips per year, or over 11 million trips per day. Some good places to ramp up investments would be full-fledged BRT in the tri-state region (along the Tappan Zee Bridge corridor, in New York City, in Bergen County, New Jersey and in Suffolk County on Long Island), the existing New York City subway system , all of which are in dire need of repairs, and all of which alleviate road congestion.

But the economic benefits of increased funding for the New York City metro area stretch beyond the region’s physical limits. Investment in rail infrastructure in New Jersey, New York and Connecticut also benefits Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor and Acela lines, which connect four of the nation’s 10 largest metropolitan areas, and generates $3 trillion in economic activity each year.

One piece of at-risk infrastructure along the Northeast Corridor that could weigh down the region’s economy if not addressed soon is the need for greater redundancy in the North River tunnels, which would have been upgraded if the Access to the Region’s Core project weren’t shortsightedly scuttled by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie in 2010.

Clearly we need to be connecting people both within cities and between cities. As City Observatory pointed out last year, the World Bank’s chief economist Paul Romer is a strong advocate for this type of economic investment:

Romer has been a strong advocate of cities, and has pointed out the direct relationship between urbanization and economic and productivity growth. [emphasis ours] Across countries, within countries, and over time, a higher degree of urbanization is strongly correlated with greater economic output.

Regionally, we also see a similar yet less drastic inability to prioritize. Take the Port Authority’s recently released capital program, which we noted last fall, lacks prioritization.

[P]lanning cannot and should not be done “squeaky wheel” style where the most visible problems get top priority… Rather, we ought to be setting goals for the region and engaging in regionally-cooperative planning that takes a big picture approach to deal with regional mobility needs.

The same sort of thinking seems to be going on at the state level too. In our region, state governments continue to under-fund transit, to the detriment not only of people who rely on the transit service, but also to their own climate change goals:

[T]he three states in the region continue to invest in highway expansion while transit needs are deferred (or ignored) and wishful thinking about technological solutions from the future abounds:

– In New York, emission reduction objectives of downstate transit projects have been undermined by efforts to subsidize driving on the New York State Thruway.

– The Port Authority’s most recent capital plan only included about 10 percent for transit projects.

– In 2011, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie pulled out of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, and in 2010, he killed the Access to the Region’s Core rail tunnel project.

– In Connecticut, Governor Malloy has released a long-term transportation plan that includes billions for widening I-95 and I-84.

– New Jersey’s Transportation Trust Fund is staring down insolvency, which has led to higher NJ Transit fares and more bus and train commuters thinking about driving to work instead.

– When New York and Connecticut committed to the Under 2 MOU, the main focus was on renewable energy and electric vehicles, not transportation infrastructure or land use policy. This lack of attention to how people move and how communities are designed is mirrored in New York and Connecticut’s energy plans.

– Although New Jersey has not signed onto the Under 2 MOU, it also has an energy master plan. But it doesn’t mention public transit once, and is focused instead on emerging technologies and alternative energy vehicles.

The inability to prioritize is real and so are its effects: bad subway service, even worse bus service, broken rails, derailments, extensive delays, lack of redundancy and, ultimately, a threat to the engines of the economy, not to mention the average commuter’s ability just to get to work on time.

Mobilizing the Region is published by the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, a 501(c)(3) non-profit policy advocacy organization. If you’d like to support our work, please make a tax-deductible donation today.

What percentage of the total cost of providing transit should be paid by the rider? How does that compare to the total cost of providing roads for the automobile offset by fuel excise tax and motor vehicle fees?

[…] Watch the Failure of Federal and State Transport Policy Play Out Before Your Eyes (MTR) […]