The Central Avenue corridor connecting Albany and Schenectady has been in the news lately after four-year-old Ashiqur Rahman was killed by a turning garbage truck at the intersection with Quail Street in Albany. Pedestrian deaths and injuries are nothing new to Central Avenue, long known as one of the Capital District’s most dangerous roads for pedestrians. And although efforts are underway to make this urban arterial more friendly to users of all types, it seems that opportunities to transform it into a truly multimodal corridor are being ignored.

Central Avenue, originally known as the Albany Schenectady Turnpike, once had a streetcar line, making it a truly multimodal corridor. But when the streetcars were removed in 1946, the renamed Central Avenue was expanded to its current auto-centric format, with two travel lanes in each direction and a center turn lane for much of its length.

Today, in Albany and Schenectady, Central Avenue runs through dense urban neighborhoods with significant pedestrian traffic, while in Colonie and Niskayuna, it runs through areas that were originally built out as streetcar suburbs. And in other locations, Central Avenue carries traffic generated by regional shopping destinations. And yet, the mobility solutions applied the New York State Department of Transportation and local jurisdictions have been essentially uniform and largely unchanged since the roadway’s auto-centric postwar conversion. Predictably, that single-minded focus on vehicular throughput has led to poor outcomes for other users.

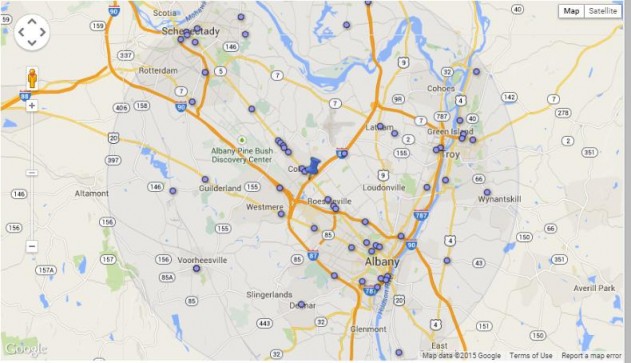

Pedestrian deaths in the Capital District, not unlike the rest of the tri-state area, are largely concentrated along arterial roads like Central Avenue. Analyses by Tri-State and Smart Growth America illustrate how many of the area’s pedestrian crashes were clustered along Central:

Efforts to make Central Avenue safer appear to be falling short. Certainly the Capital District Transportation Authority’s BusPlus service has provided new mobility for non-drivers along the corridor, but if anything, greater demand for transit, walking and biking has led to more crashes. NYSDOT’s response to the escalating fatality total has been the launch of a “See! Be Seen!” campaign, which has provided little else besides new “beg buttons” for pedestrians.

The Central Avenue corridor is a complex urban environment that requires design and engineering — not simply educational campaigns. So what can NYSDOT do to improve safety on this corridor? For starters, the section of Central between Henry Johnson and Manning Boulevards in Albany—where Ashiqur Rahman was killed—carries only 17,700 cars per day, making it a perfect candidate for a 4-to-3 road diet. The suburban areas will be a tougher nut to crack, but we can start by replacing those beg buttons with automatic pedestrian signals and the addition of crosswalks to reduce long distances between marked crossings.

Pedestrians will continue to be at risk traveling along Central Avenue until state and local policymakers face the critical decision at hand: continue to pursue the relentless auto-centricity of decades past, or recognize its escalating toll and begin to treat not just the symptoms, but also the cause.

[…] I’m now interning for the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, where you should check out my debut blog post), I’ve finally found the time here for Part 2, a breakdown of Albany’s challenges and […]

[…] Missions 12527 Central Ave., Suite 163 Minneapolis, MN 55434 […]

[…] the pedestrian environment, with a special emphasis on bus corridors. MTR has already covered the need for safer pedestrian design along Central Avenue, which carries the BusPlus Red Line. Many […]

[…] crashes, but the decision to prioritize vehicular throughput over pedestrian safety was certainly no accident. High-speed, multi-lane suburban arterials can’t be made safe for walking simply through […]